About this event

4 days 1 hour

- Mobile eTicket

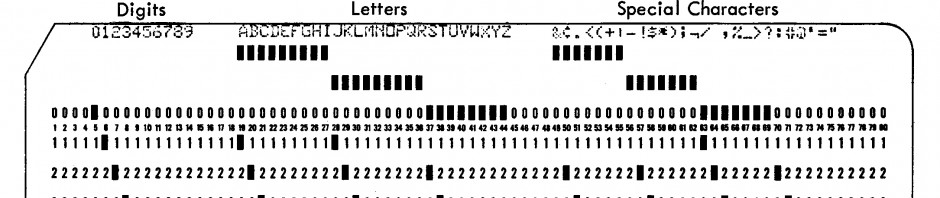

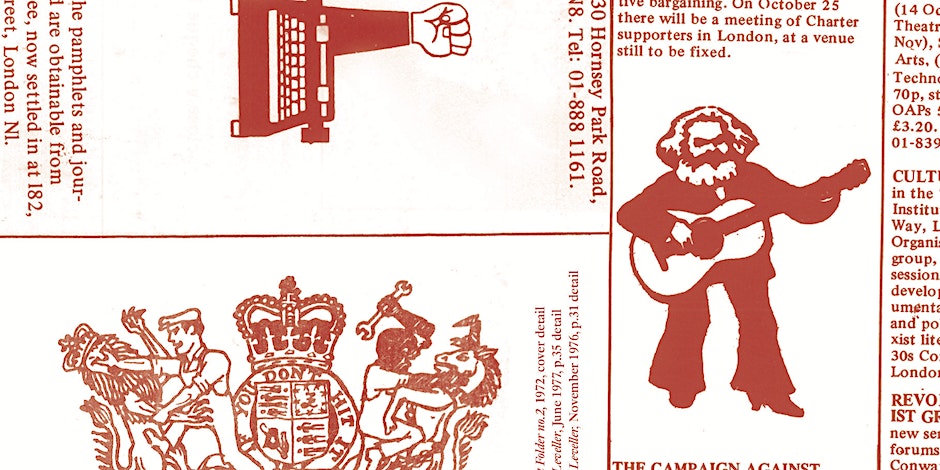

Practices and Research in Living and Unfinished Archives is a 3 day workshop bringing together practitioners, researchers and students from different disciplines and institutions, around an interest in archival material. Based at MayDay Rooms in London, and working with political material from the collections (printed ephemera produced by political groups, collectives and post-1968 social movements organisations), the workshop aims to introduce participants to different creative approaches to research in the archive. Considering the archive not as ‘an inert museum of dead works’ but a living organism whose construction ‘must be seen as an on-going, never-completed project’, the workshop’s aim is to explore archiving and archival research as an unfinished and open-ended process.

Through the workshop, invited guests (artists, photographers, designers, writers, archivists and librarians) introduce participants to different ways to work with archival material across posters, pamphlets, newsletters, magazines, documents, formats and production processes that characterised this kind of publishing through history. Participants will engage in group discussions, collective research, speculation, and interpretation of documents part of the collections, and produce creative responses, with the opportunity of contributing content to a publication.

We’d like workshop participants to come from a range of different practice based disciplines including, art and design, illustration, graphics, photography and media. Undergraduate and postgraduate students from other disciplines but with an interest in radical politics and publishing, are also invited to apply to the workshop.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

To apply for a place at this free workshop please sign up using eventbrite / email questions to g.rossi@greenwich.ac.uk

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Workshop led by Tamara Rabea Stoll, Anthony Iles, Guglielmo Rossi

Tamara Rabea Stoll [short 2 line bios here]

Anthony Iles [short 2 line bios here]

Guglielmo Rossi is a graphic designer and educator based in London. He runs a small design studio called Bandiera (bandiera.co.uk), teaches at the University of Greenwich, and is part of the Print! Research Group based at MayDay Rooms.

MayDay Rooms is an archive, resource space and safe haven for social movements, experimental and marginal cultures and their histories. Our building in the centre of London contains an archive of historical material linked to social struggles, resistance campaigns, experimental culture, and the expression of marginalised and oppressed groups

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Friday 8 September (3:00 to 4:30pm)

— Welcome and Introduction to the archive at MayDay Rooms

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Monday 11 September (10.30 to 4.30pm)

— Morning presentation + Workshop activities

— Lunch break + discussion

— Afternoon presentation + Workshop activities

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Tuesday 12 September (10.30 to 4.30)

— Morning presentation + Workshop activities

— Lunch break + discussion

— Afternoon presentation + Workshop activities

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Wednesday 13 September (3:00 to 4:30pm)

— Conclusion + publication proposition